British newspaper barcodes explained — and automated

Barcodes can be pretty mystifying from the outside, if all you’ve got to go on is a set of lines and numbers, or even magic incantations for the software that produces them.

Despite working at a place where we produce a product with a new barcode every day, I didn’t understand how they were made up for years.

But they’re fairly straightforward, and once you know how they work it’s quite simple to produce them reliably. That’s important because getting a barcode wrong can cause real problems.

Barcode problems

In the case we’ll look at here, daily newspapers, an incorrect barcode means serious headaches for your wholesalers and retailers, and you’ll likely and entirely understandably face a penalty charge for them having to handle your broken product.

I know because, well, I’ve been there. In our case at the Star there were two main causes of incorrect barcodes, both down to people choosing:

- the wrong issue number or sequence variant;

- the wrong barcode file.

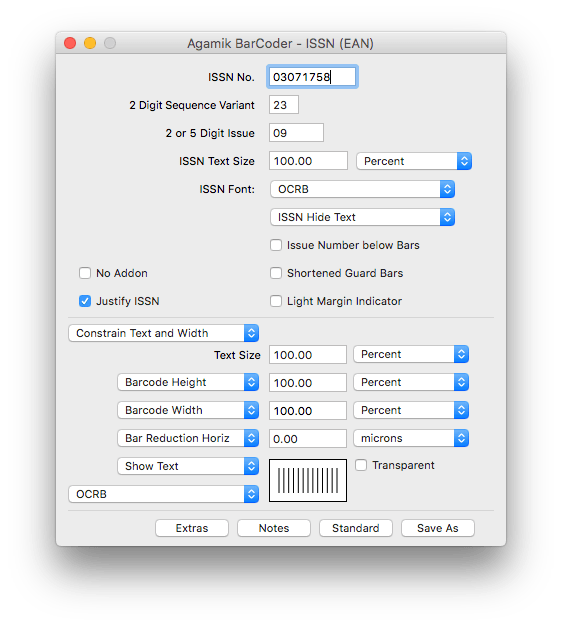

We’ll talk about the terminology shortly, but we can see how easily problem number one can occur by looking at the interface of standard barcode-producing software:

Now, Agamik BarCoder is a nice piece of software and is very versatile. If you need to make a barcode it’s worth a look.

But look again at that interface — it’s not intuitive what you need to do to increment from the previous day’s barcode, the settings for which are saved in the application. It’s very easy to put in the wrong details, or accidentally reuse yesterday’s details.

Second, it produces files with names such as ISSN 03071758_23_09 — a completely logical name, but the similarity between the names and the fact you have to manually place the file on your page makes it easy to choose the wrong barcode, whose name will likely differ only by one digit to the previous day.

That isn’t helped by Adobe InDesign by default opening the last-used folder when you place an image. At least once, I’ve made the barcode first thing in the morning and accidentally placed the previous day’s barcode file.

One of the suggestions we had after we printed a paper with the wrong barcode was to have the barcode checked twice before the page is sent to the printers. This is an entirely sensible suggestion, but I know from experience that — however well-intentioned — “check x twice” is a rule that will be broken when you’re under pressure and short-staffed.

It’s far more important to have a reliable production process so that whatever makes it through to the proofreading stage is certain to be correct, or as close as possible.

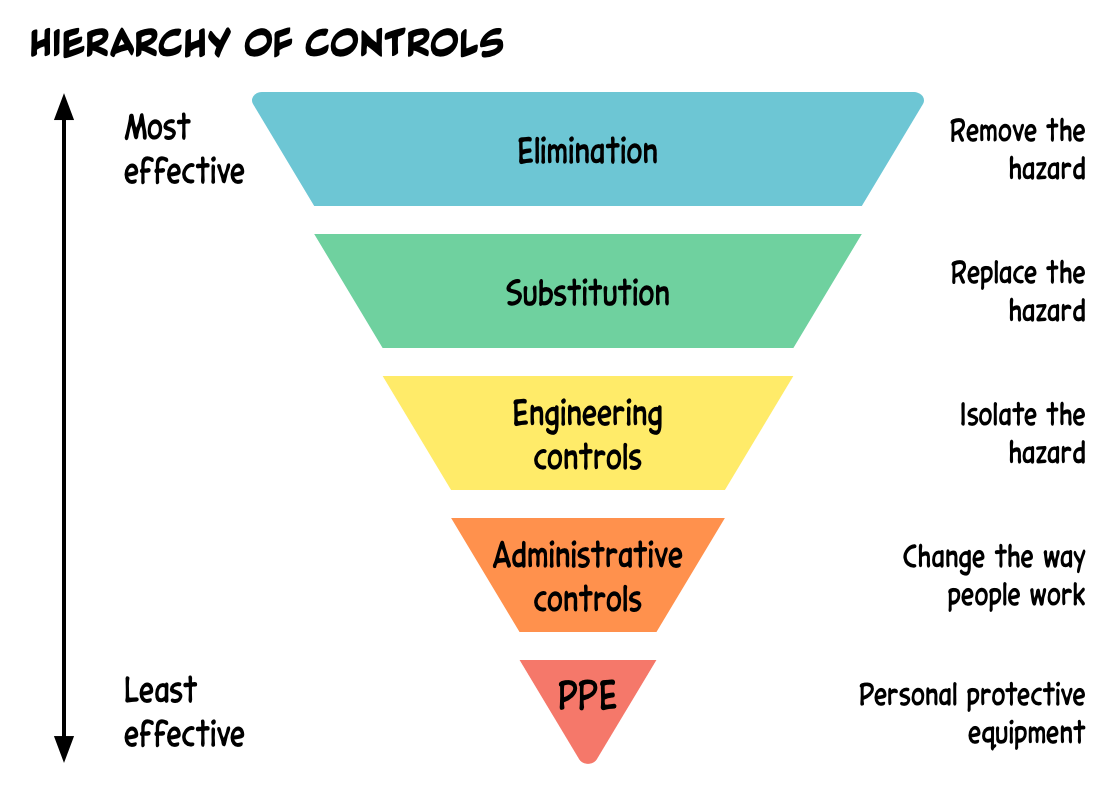

We can understand this by looking at the hierarchy of hazard controls, which is useful far outside occupational health and safety:

“Check twice” is clearly an administrative control — changing the way people work while leaving the hazard in place. An engineering control in our case might be to have software check the barcode when the page is about to be sent to the printers (something we do on PDF export by inspecting the filename). We want to aim still higher up the hierarchy, eliminating or substituting the hazard.

But to reach that point we need to understand the components of a barcode.

Barcode components

Barcodes are used all over the place, so it’s understandable that some terms are opaque. But picking a specific case — daily newspaper barcodes here — it’s quite easy to break down what they mean and why they’re important.

The information here comes from the barcoding guidance published by the Professional Publishers Association and Association of Newspaper and Magazine Wholesalers. It’s a very clear document and if you’re involved in using barcodes for newspapers or magazines you should read it. (Really, do read it, as while I’ll try to bring newspaper barcodes “to life” below, there’s a lot of information in there that I won’t cover — such as best practice for sizing.)

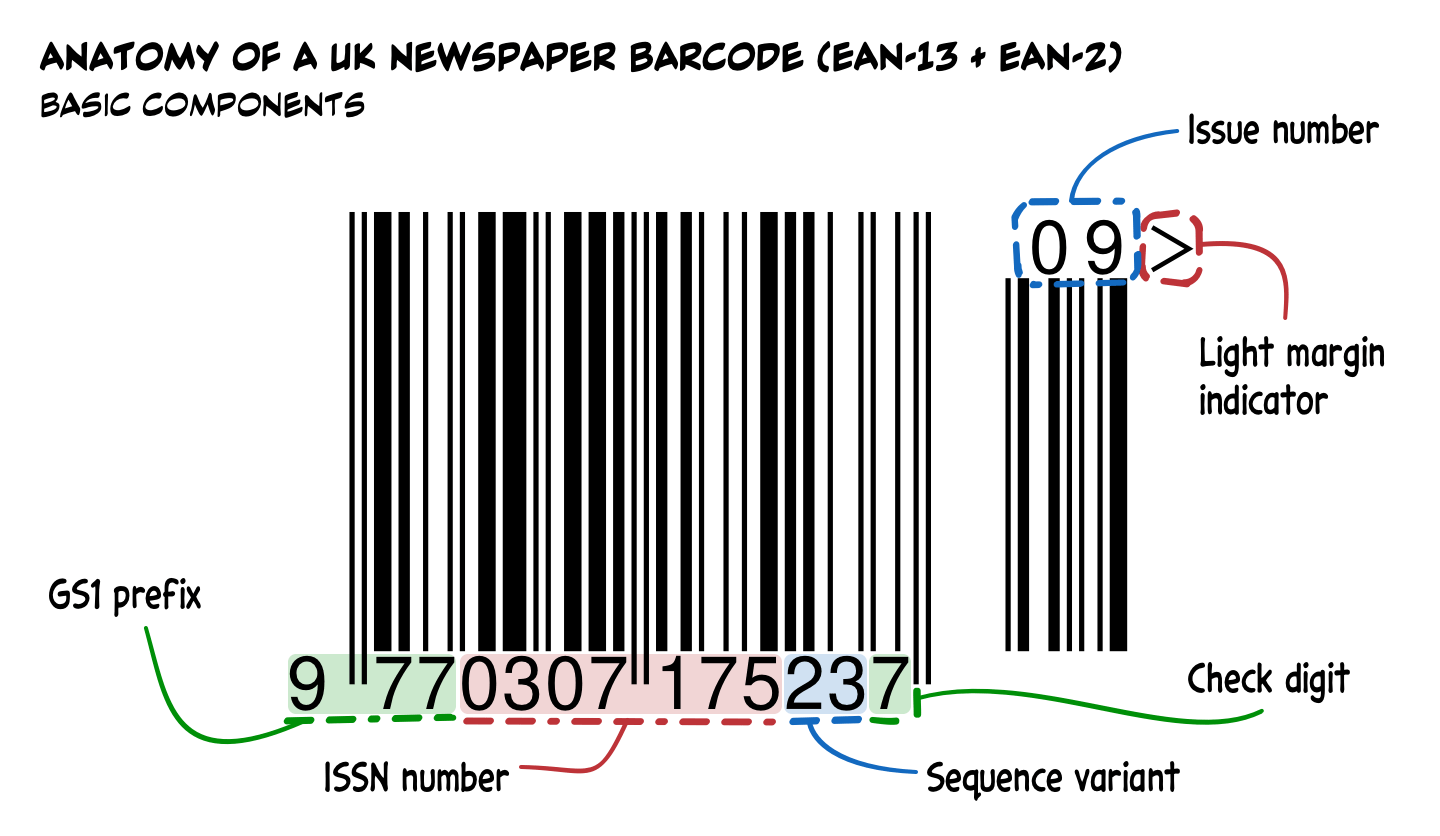

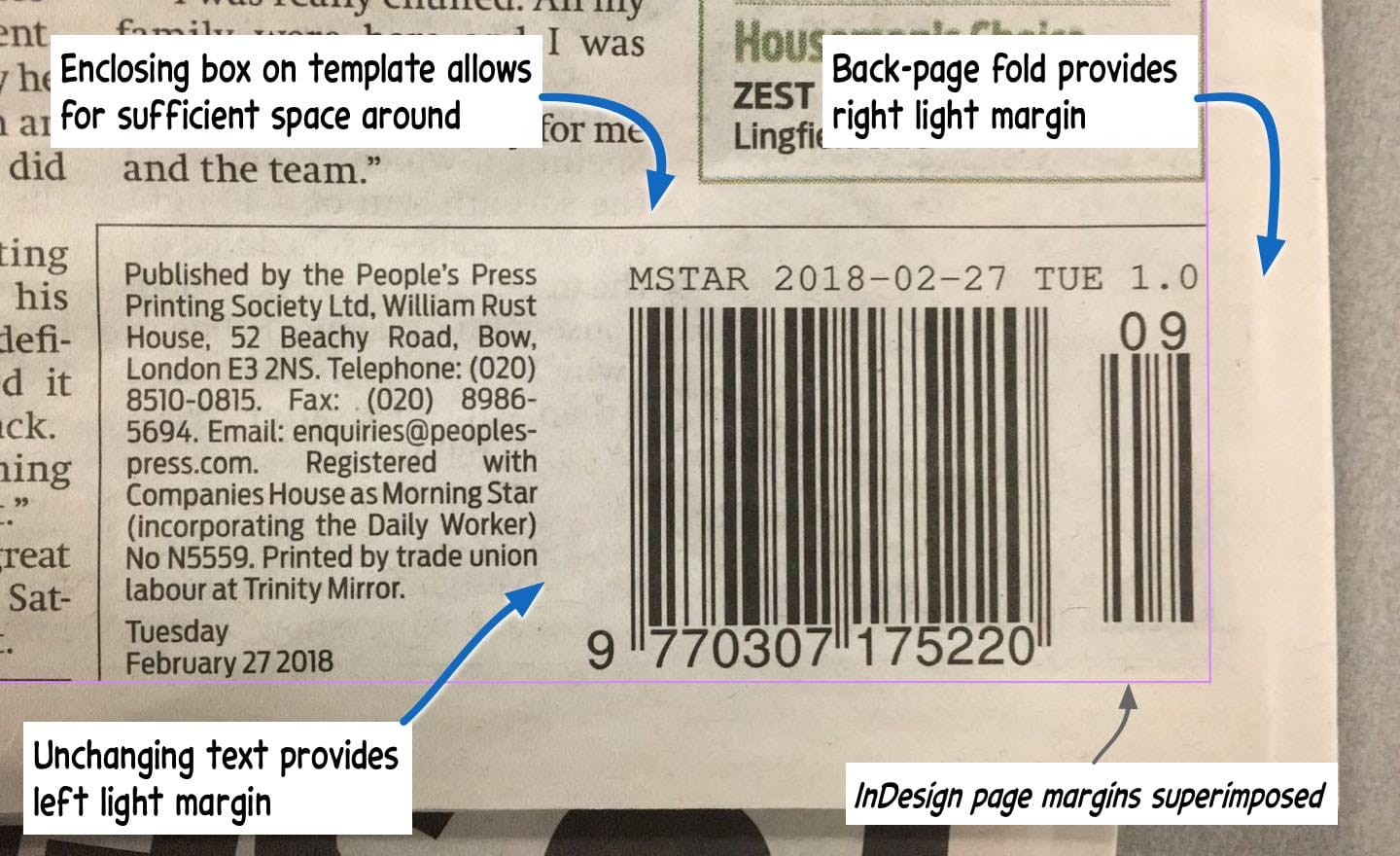

Let’s start off by examining a typical newspaper EAN-13+2 barcode, using the terms that you’ll find in the PPA-ANMW guidance:

You’ll see at first that it’s clearly made up of two components: the largest is a typical EAN-13 barcode with a smaller EAN-2 on the right.

Reading left-to-right, we have the GS1 prefix to the barcode number, which is always 977 for the ISSN numbers assigned to newspapers and magazines.

Next is the first seven digits of the publication’s ISSN number — the eighth digit isn’t included because it is a check digit and is redundant because the EAN-13 includes its own check digit.

That check digit follows a two-digit sequence variant, which encodes some information about the periodical. On the right, above the EAN-2, is the issue number. This is used in different ways depending on the publication’s frequency.

Lastly is a chevron, which is used to guard some amount of whitespace on the right-hand side to ensure the barcode reader has enough room to scan properly. (The leading 9 performs the same function on the left.) This is optional.

In practice

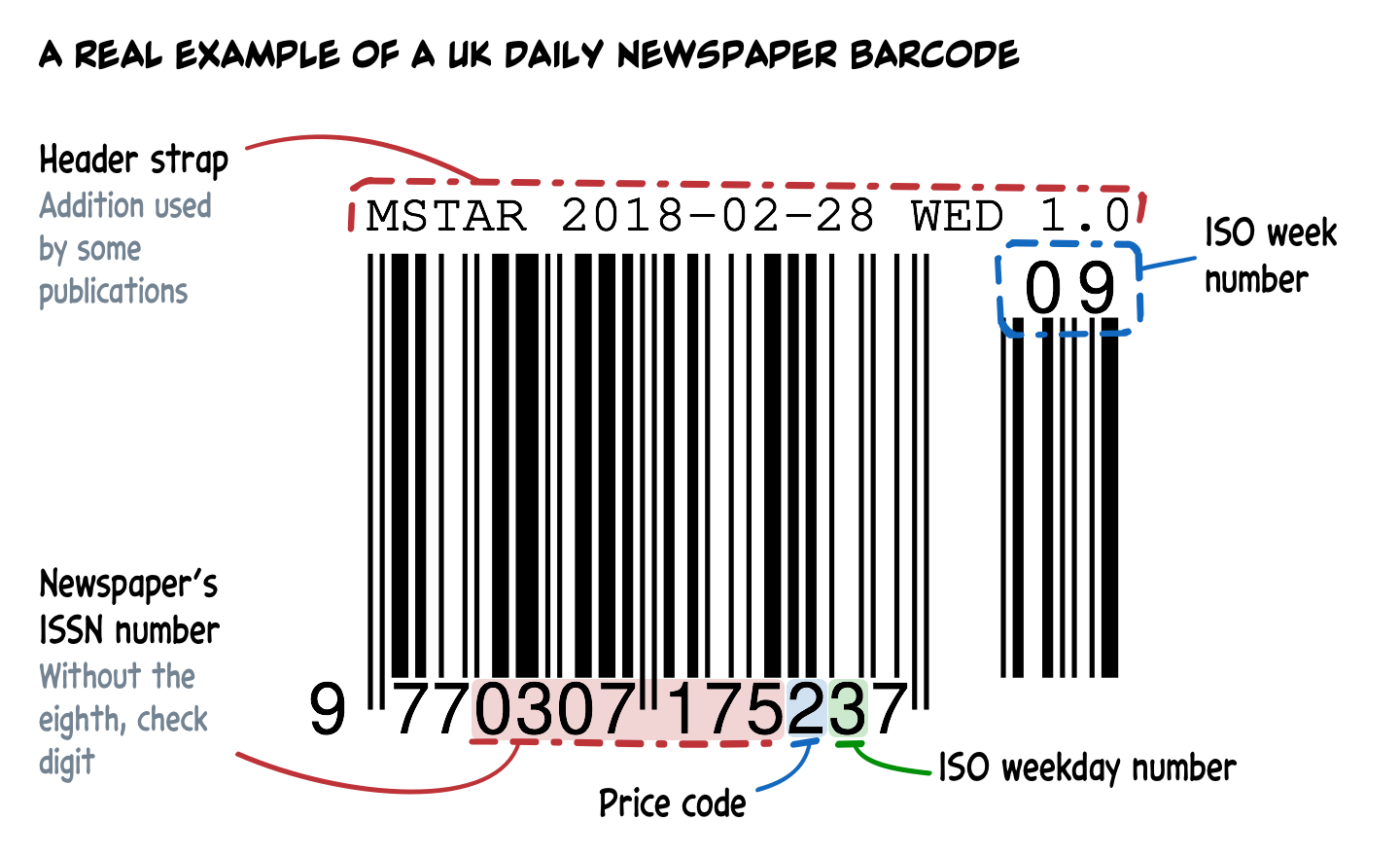

Now let’s look at a real barcode, see which elements we have to think about, and how they fit together.

Now let’s start with the elements that were present on the basic ISSN barcode.

ISSN number

Your newspaper’s ISSN appears after the 977 prefix. The Morning Star’s ISSN is 0307-1758, but the 8 at the end of that is a check digit, used to detect errors in the preceding seven digits. This is removed because it’s unnecessary as the 13th digit of the EAN-13 is a check digit for all 12 preceding digits. So only the front seven digits of the ISSN appear in the bar code.

Sequence variant

For daily newspapers the sequence variant provides two pieces of information.

The first digit is a price code, which indicates to retailers what price they should charge. The code is dependent on the publication — you can’t tell from the price code alone what price a newspaper will be. For the Star, we currently use price codes 2 (£1) and 4 (£1.50).

The second digit is the ISO weekday number. Monday is ISO weekday 1, through to Sunday as 7.

So by looking at the sequence variant in this barcode, we can tell that it’s the paper for Wednesday (ISO weekday 3) and sells at whatever price code 2 corresponds to in the retailer’s point-of-sale system.

When you introduce a new price, typically you use the next unused price code. We recently increased the price of our Saturday paper from £1.20 (price code 3) to £1.50 (price code 4).

Issue number

The issue number appears above the EAN-2 supplemental barcode. For daily newspapers this corresponds to the ISO week containing the edition. Note that this may differ from, say, the week number in your diary. New ISO weeks begin on Monday.

Modern versions of strftime accept the %V format, which will return a zero-padded ISO week number. In Python the date and datetime classes have an .isocalendar() method which returns a 3-tuple of ISO week-numbering year, ISO week number and ISO weekday number.

Header strap

The line printed above the barcode is technically not part of the barcode itself, and different publications do different things. It’s common not to print anything, and for years we didn’t either, but I think it’s quite useful to print related information here to help whoever has to check the barcode before the page is sent for printing.

Note that in this example, all the information printed above the barcode is referred to in the barcode itself (except the year). I use this space to “decode” the barcode digits for human readers.

This was suggested to me by our printers (Trinity Mirror), who do something similar with their own titles.

Light margin indicator

Eagle-eyed readers will spot that the chevron used to guard whitespace for the barcode scanner is missing from the right-hand side. The PPA-ANMW guidance does urge that you include the chevron, but its absence as such won’t cause scanning problems.

It’s straightforward to guarantee enough space around the barcode by carefully placing it in the first place. Our back-page template reserves a space for the barcode, along with some legally required information, which is big enough to make the chevron unnecessary. You can see this in the image below:

The main block of text on the left of the barcode doesn’t change. The date below it does, but it’s been tested so that even the longest dates provide enough space. (The longest date in consideration being the edition of Saturday/Sunday December 31-January 1 2022-2023.)

The superimposed purple lines show where the margins would appear in Adobe InDesign, with the barcode in the bottom-right corner. This section is ruled off above to prevent the encroachment of page elements, with the understanding that page items must end on the baseline grid line above the rule (which itself sits on the grid).

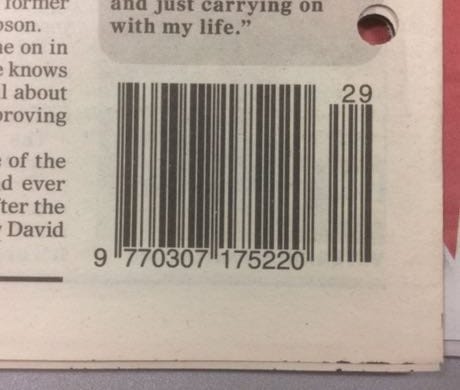

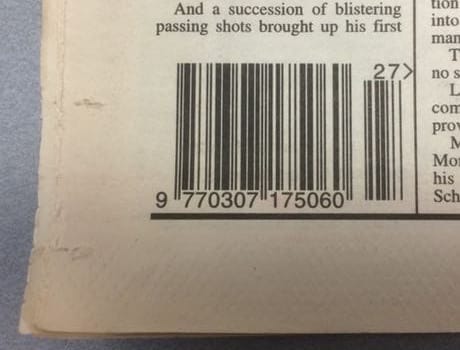

(As you can see from the smaller photos, this wasn’t always the case. The barcode often had page elements very close by, and did not have its own clear space. At this point, the barcode was also produced at a smaller size to fit within one of the page’s six columns.)

The “inside margin” on the right-hand side of the page (remember that the back page is in fact the left-hand page of a folded spread) provides an additional light margin. However, note that you still need an adequate distance from the fold itself:

“it is recommended that the symbol should not be printed closer than 10 mm from any cut or folded edge” (PPA-ANMW)

Our inside margin is 9mm, with the edge of the EAN-2 symbol roughly 1.5mm further in, for a total 10.5mm. While it appears that there’s bags of space, we’re still only just within the recommendations.

You might want to put the barcode on the outer edge of the back (the left-hand side) as the margin there is deeper (15mm in our case), but I would be very cautious about doing so. I’ve seen enough mishandled papers with bits torn off that I prefer the safety of the inside of the sheet.

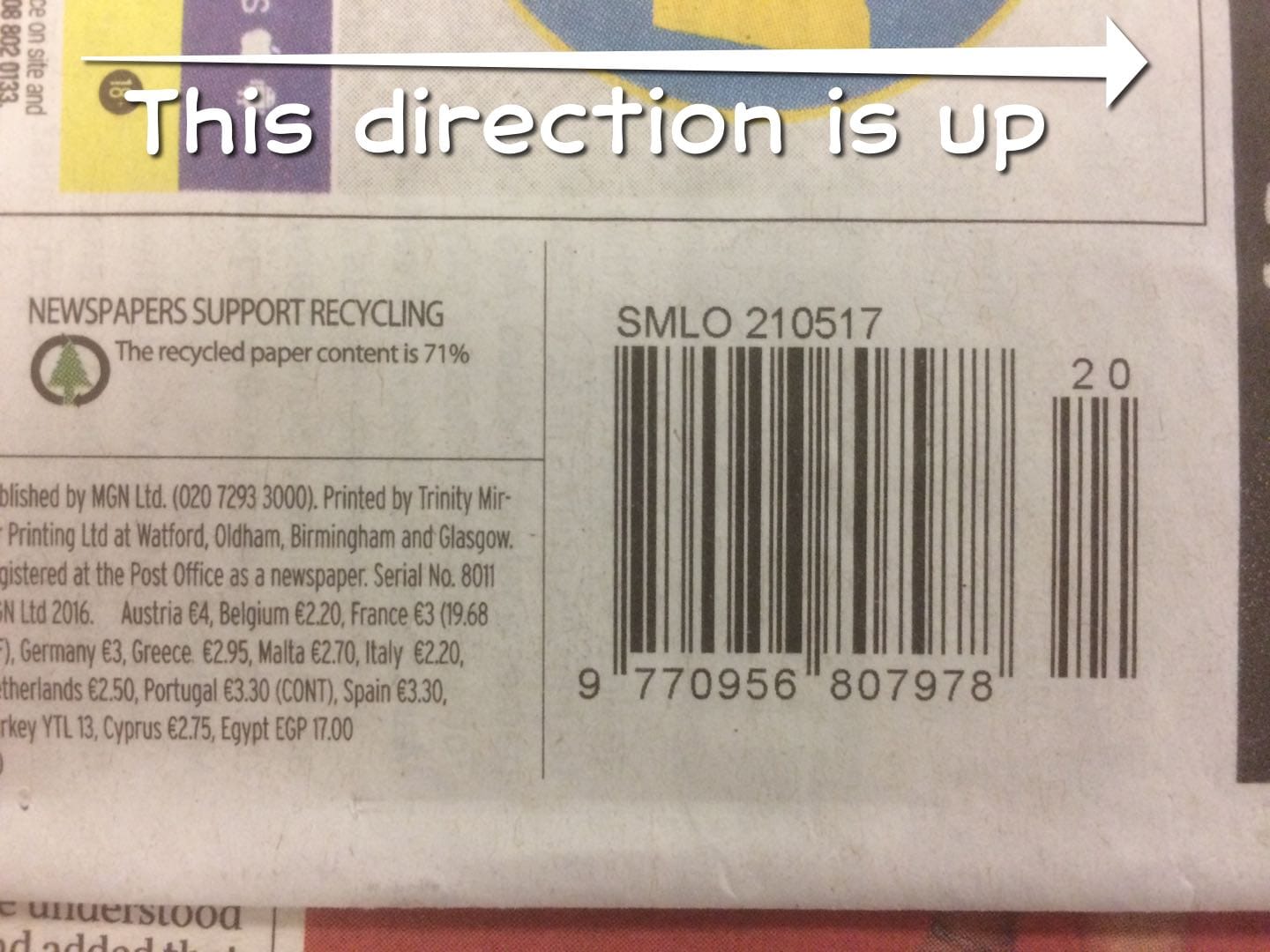

You can see similar considerations at work when you look at how other papers place their barcodes. This example of the Sunday Mirror is quite similar to the Morning Star above, but rotated to make use of the more abundant vertical space:

(You can also see the use of a strap above the barcode, with the title name (SM, Sunday Mirror) and date (210517). I’m not sure what LO means, but it could mean London, if this is used as a way of identifying batches from different print sites.)

The Times and Financial Times also take this approach of cordoning off a space. Neither use a header strap (not unusual), though I am confused by the placement of the chevron in the FT’s barcode. It should be outside of the symbol area to reserve the space, though a lack of space is certainly not an issue.

Dedicating some space for the barcode is important because it means that there won’t be any compromises made day-to-day. You’ll want to take into account the recommended size and magnification factors in the PPA-ANMW guidance if adjusting page templates.

One of the changes we made was to abandon the reduced-size barcode (to fit within a page column), which then meant that something else was needed to fill out two columns to justify the space. But — as seen in the examples from other papers — it might be that having some amount of additional blank space around the barcode is an easy sell anyway.

Automation

Where these considerations really come in is when you automate the creation and setting of the barcode, because they can be thought about once, agreed and then left untouched as the system ticks along.

This gets us to the substitution level of the hierarchy of controls — we’re looking to do away with the hazard of human error in barcode creation, but ultimately we replace it with another hazard, ensuring that an automated system works correctly. We’ll return to this hazard briefly after taking a look at the automation program itself.

The code is available on GitHub. I won’t be including large chunks of it because it’s all fairly nuts and bolts stuff (and this post is long enough already!).

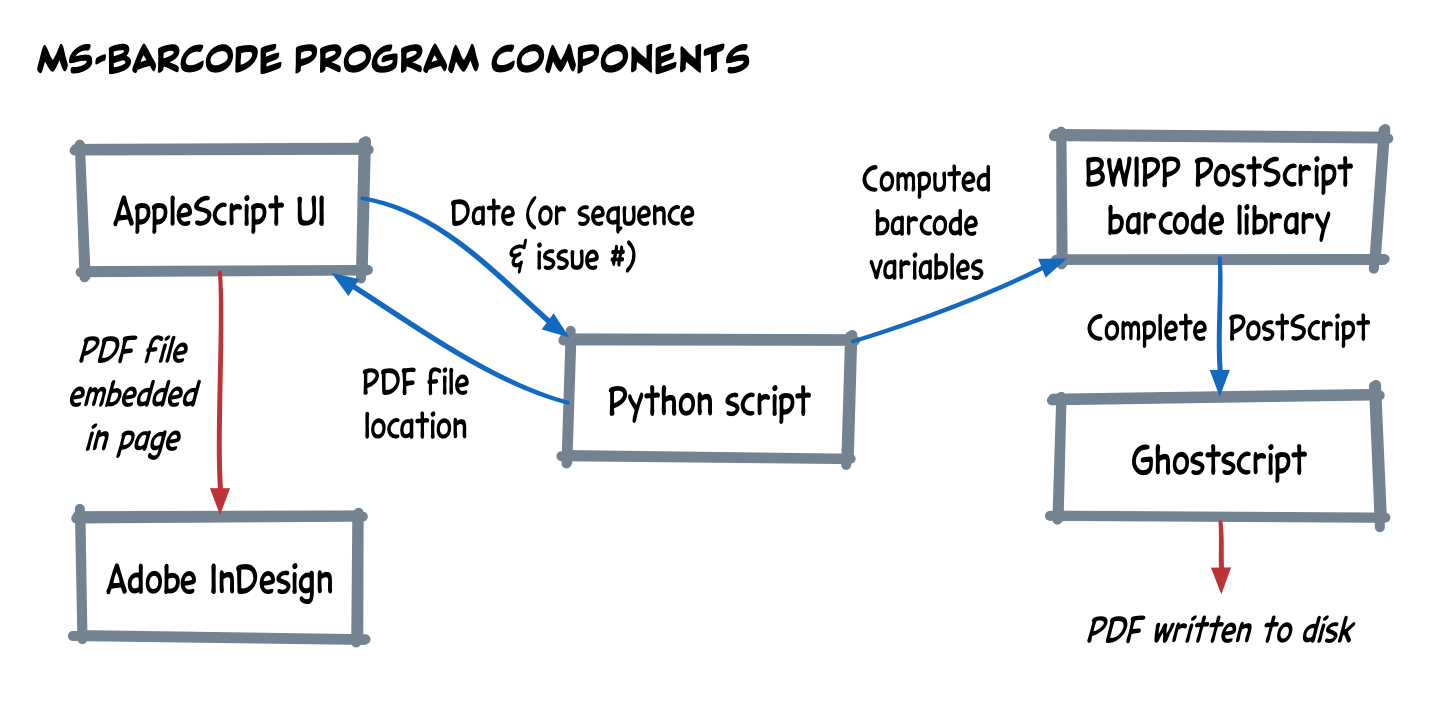

The structure is fairly straightforward. Like a lot of my more recent automation projects at work, it has an AppleScript user interface which passes arguments to a Python command-line program, which either performs some action itself or returns a value for use in the AppleScript program.

In this case, the Python program computes the correct sequence variant (price and weekday) and issue number (ISO week) — along with a human-readable header — and embeds them in a PostScript program that uses the brilliant BWIPP barcode library.

This PostScript is processed into a PDF file by Ghostscript, and the path to this barcode PDF is handed back to the AppleScript program so that it can embed it in a labelled frame in InDesign. (To embed files in an InDesign document you’ll need the unlink verb. Yes, I thought that meant “delete the link” at first as well.)

Here’s a diagram to show the flow through the program (forgive the graphics, I’m learning how to use OmniGraffle):

Cloc tells me that the main Python file has a whopping 104 lines of code, and there are 264 lines of code in the related unit tests.

Really all of the heavy lifting is done by BWIPP, a cut-down version of which is included in the ms-barcode repository (just ISSN, EAN-13 and EAN-2). The entirety of my “own” PostScript is this (where the parts in braces are Python string formatting targets):

1%!PS

2({bwipp_location}) run

3

411 5 moveto ({issn} {seq:02} {week:02}) (includetext height=1.07)

5 /issn /uk.co.terryburton.bwipp findresource exec

6

7% Print header line(s)

8/Courier findfont

99 scalefont

10setfont

11

12newpath

1311 86 moveto

14({header}) show

15

16showpage

The bits that you may need to fiddle with, if you want to produce a different-sized barcode, are the initial location the ISSN symbol is drawn at (line 4) and height=1.07 on the same line.

You’d also want to adjust the size specified to Ghostscript, which is used to trim the resulting image — the arguments are -dDEVICEWIDTHPOINTS, and -dDEVICEHEIGHTPOINTS.

I don’t know enough about PostScript (or Ghostscript) to give good general guidance about getting the right size. My advice would be to start with what I have and make small adjustments until you’re heading in the right direction (which is exactly how I settled on the arguments currently in use).

What I would emphasise is that if you have trouble with the existing Python modules that wrap BWIPP, it’s not difficult to use the PostScript directly yourself. Really, look back at the 16 lines of PostScript above — that’s it.

Wrapping up

By automating in this way, we now have a method where the person responsible for the back page simply clicks an icon in their dock, presses return when asked if they want the barcode for tomorrow, and everything else is taken care of.

Going back to our earlier discussion of hazards, I think we’ve reached the substitution stage rather than the elimination stage.

We have eliminated human error in choosing the components of the barcode, but we’ve done it by substituting code to make that decision. That’s still a good trade, because that code can be tested to ensure it does the right thing.

And then, you can go back to not worrying about barcodes.